The Tresckow Plans

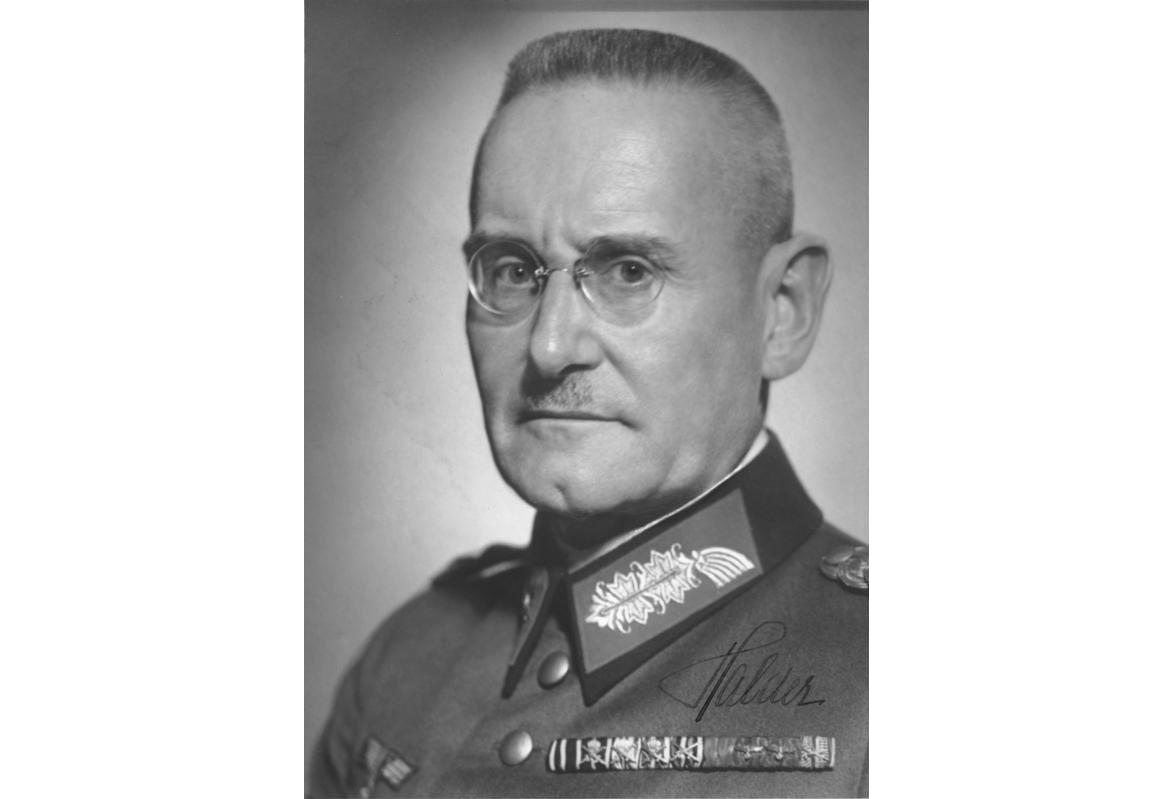

Hans Oster was not the only top-level member of the German military establishment to plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler and trigger a government coup. As early as 1941, Oberstleutnant Henning von Tresckow and others in the Army Group Center were “prepared to do anything” to support the German Resistance movement if it initiated a coup against the Nazi regime. (Joachim Fest: Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 181)

Two years later, Treskow himself was organizing the military Operation Flash bombing attempt on Hitler’s life and helping Claus von Stauffenberg plan the July 20, 1944 Plot or Operation Valkyrie, the focus of the 2008 film starring Tom Cruise and the subject of the next Historka posts.

https://alchetron.com/Henning-von-Tresckow

Early Years

Tresckow supported the Nazis in the 1920s, campaigning for the party among army officers and denigrating opponents as hopeless reactionaries. (Plotting Hitler’s Death) That began to change in the summer of 1934 after the Night of the Long Knives purged the ranks of the SA’s Storm Troopers using what Tresckow called “methods of a gang of bandits” (Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 53) and Hitler’s actions brought the military under his control.

Tresckow’s opposition to Hitler intensified after the invasion of Poland when he learned about Einsatzgruppen’s “state-sanctioned murder squads” (Plotting Hitler’s Death p 119). In one case, an Einsatzgruppen squad had lined up naked men, women, and children at the edge of a pit, made them climb into the dirt and lie face down while eight SS shot them to death. Over the course of two days, the operation continued until 3000 people had been killed. (John Grehan, The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 139)

The decree on military law and Commissar Order of June, 1941, were a call to action for Tresckow. Under the new decree on military law, military courts no longer had power to punish perpetrators for committing crimes against enemy civilians. The Commissar Order required German soldiers to shoot and kill any Soviet Communist Party commissar who was taken prisoner. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/commissar-order

Tresckow not only pushed for a retraction of the decrees: “If we don’t convince the field marshal to fly to Hitler at once and have these orders canceled, the German people will be burdened with a guilt the world will not forget in a hundred years.” (Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 175)

He also became the first General Staff Army officer on the frontlines of the war to form his own resistance cell and try to use military resources to remove Hitler and overthrow his regime.

The Barbarity of Barbarossa

Tresckow was the General Staff officer for the German Army’s Centre during the Barbarossa campaign, the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. He consequently was well aware of the actions taken on the Eastern Front: the ruthless elimination of partisans in battle or while escaping and the “annihilation of [civilian] attackers.” The German high command’s orders could not have been more explicit: “Every officer in the German occupation in the East … will be entitled to perform executions(s) without trial, without any formalities, on any person suspected of having a hostile attitude towards the Germans.” (The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 138)

Tresckow saw a chance to mount an attack on Hitler and his regime in the winter of 1941-42 while the Soviet counteroffensive was stopping German troops in their tracks or gaining ground against them and other, powerful German military leaders were warming to the idea of removing Hitler from command.

As others before them, Tresckow and his group of military conspirators at first considered, then rejected, the idea of a sniper attack or a handgun shot at close range. Hitler was too heavily protected and his schedule was too erratic to pick a likely time and place, and too few candidates were willing to take the chance.

A plan to place a bomb in Hitler’s parked automobile while he was visiting the front failed when none of the conspirators could get close enough. Another barely got past the talking stage—a military unit would fire on Hitler “if an opportunity presented itself.” (Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 193)

Tresckow came up with a more satisfactory plan of attack—planting and detonating a bomb on Hitler’s aircraft. The bomb could be placed without any of the conspirators being suspected, and it could be detonated while the plane was traveling over enemy territory, making it possible to blame the Soviets for the assault. (The Hitler Assassination Attempts)

What was needed—detailed drawings of the plane and its interior and explosives.

The Aircraft

The plane in which Hitler routinely traveled was heavily armor-plated, its windows made of thick bulletproof glass. A specially designed cabin for Hitler himself could be detached from the fuselage and parachuted away if the plane was disabled in any way. The aircraft also was heavily guarded by SS who searched every passenger as well as grounds crew and cleaners.

To be effective, the bomb would have to be secreted in Hitler’s cabin, which was nigh on impossible. Instead of trying to hide the bomb onboard, therefore, Tresckow and his adjutant Leutnant Fabian von Schlabrendorff decided to have it unwittingly carried on board. To house the bomb, the two created a square wooden package similar to the one that commonly carried two bottles of Cointreau.

The Explosive

The conspirators soon learned that German bombs were useless for their purpose. A German bomb could not be hidden because once activated, the fuse made a low but telltale hissing noise (William Shirer: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p 1019). They consequently turned to enemy bombs—those that had been created by the British.

The British adapted a magnetic mine into what was known as the Clam, which was encased in either a stamped sheet metal casing or bakelite plastic. The rectangular, rounded case enclosed an 8-ounce plastic explosive charge and a pair of magnets at each end. The explosive was triggered by a Time Pencil or delay fuse attached to a No. 27 detonator.

The bomb was small in size: 5.75” x 2.75” x 1.5, so it could be carried in a pocket and easily concealed. https://armourersbench.com/2020/07/19/soe-sabotage-magnetic-petrol-tank-bomb/

https://varldenshistoria.se/krig/andra-varldskriget/hitler

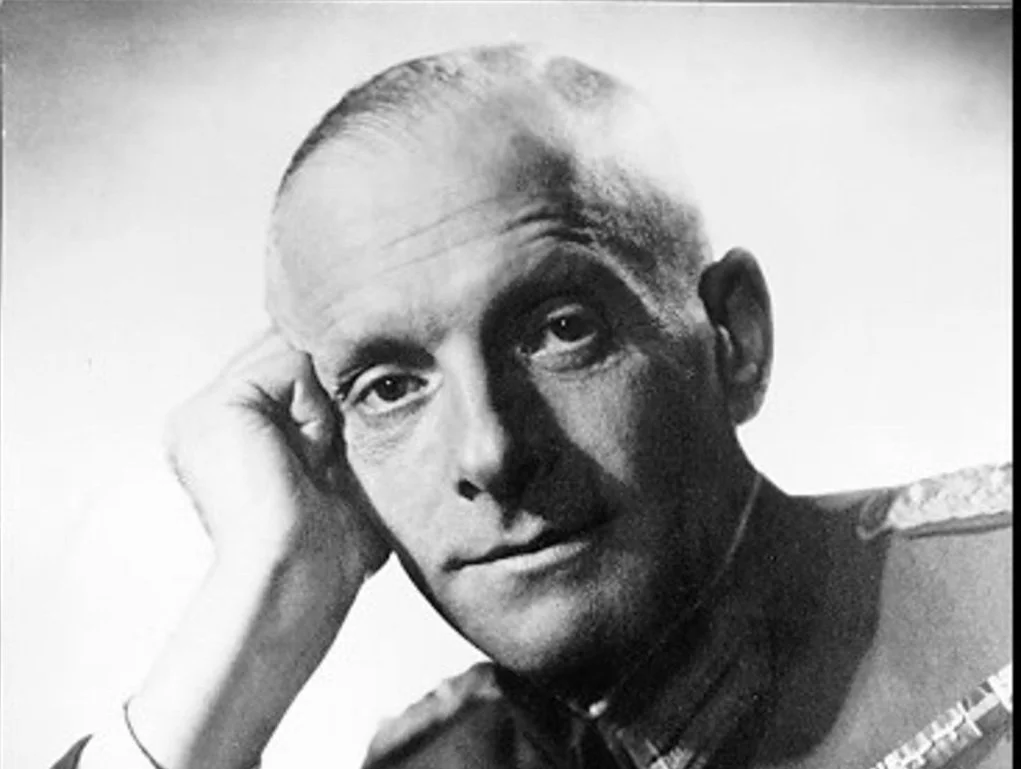

Army Col. Rudolf-Christoph Baron von Gersdorff, an Army Group Center Intelligence Officer, gathered small amounts of Plastic C, a high-energy explosive supplied by the British to underground operatives and recovered by German soldiers from captured British agents. The explosive was made largely of hexogen with other materials to prevent the hexogen from crystallizing, and it was powerful in even small amounts. Less than a pound could blow the turret off the top of a tank and hurl more than 20 yards away. (James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler, p 128)

Gersdorff then created a detonator that would trigger an explosion 30 minutes after activation. The detonator contained a glass vial that released acid into a wad of cotton until it ate through a trip wire. The trip wire then released a plunger into the explosive. (Target Hitler)

Operation Flash

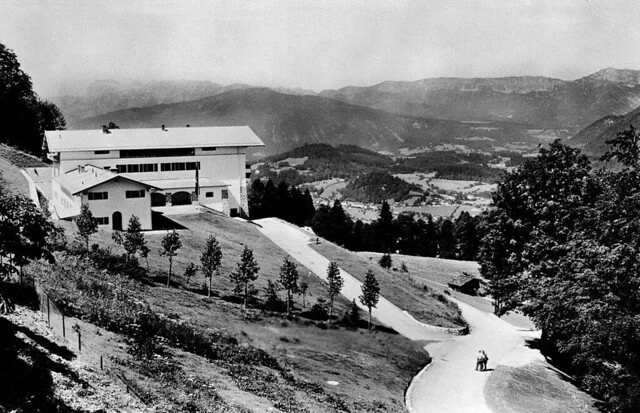

On the morning of March 13, 1943, three Focke-Wulf Condor aircraft landed on the airstrip in Smolensk. While Me.109 fighters circled overhead and prepared to land, Hitler made his way down the ladder from the exit hatch of his Condor 2600 plane. He spent the next few hours at a war conference with leaders of the campaign against Soviet Russia and a lunch during which he extolled the prowess of the German Army and predicted massive victories against Soviet troops in the coming year. (Herbert Malloy Mason, Jr.: To Kill the Devil)

https://varldenshistoria.se/krig/andra-varldskriget/hitler

Just as Hitler was approaching the aircraft for the return trip, Schlabrendorff triggered the fuse of the bomb by pressing down on the fuse with a heavy door key. He then handed the package to Col. Heinz Brandt, an aide to Hitler, who had agreed to deliver what he thought to be a package of Cointreau bottles to Tresckow’s friend Gen. Helmuth Stieff in Rastenburg. (To Kill the Devil)

Tresckow and Schlabrendorff then drove back to headquarters and waited for word. They heard nothing for two hours until a call reported that Hitler’s plane had landed safely and without incident on the return trip. To retrieve the package and make sure the bomb was not discovered, Tresckow immediately called Col. Brandt, saying he had given him the wrong package and would send Schlabrendorff to exchange it for the right one. (To Kill the Devil)

The next morning, when Schlabrendorff entered Brandt’s office to make the exchange, he was horrified to see the colonel tossing the package from one hand to the other. After leaving the office, Schlabrendorff traveled to the train station at Korschen and boarded a private compartment he had reserved for his return journey. He removed the wrapping paper, pulled out the fuse, and saw that the acid capsule had broken and eaten away the wire but the detonator had not triggered, presumably because the bomb had been stored in the cargo hold of the plane, which was colder than the main cabin. The explosive had crystallized, and the bomb had become inoperative. (To Kill the Devil, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Target Hitler, The Hitler Assassination Attempts).

Though this attempt had failed, Tresckow was not finished. He began meeting with Claus von Stauffenberg to set in motion Operation Valkyrie. (See the next Historka posts.)

Sources:

Joachin Fest: Plotting Hitler’s Death, Metropolitan Books, 1996.

James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler, Praeger, 1992.

Herbert Malloy Mason, Jr.: To Kill the Devil, W. W. Norton and Co., 1978.

John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, Frontline Books, 2022.

William Shirer: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, MJF Books, 1990.