The Oster Conspiracy Plan in 1939 and 1940

Hand-written plans for the Oster coup conspiracy (see previous posts) were destroyed or locked away in September, 1938, after the Munich accord appeared to prevent war over Germany’s moves against Czechoslovakia. But they were dusted off in 1939-40. With Britain and France now at war with Germany following the invasion of Poland, even reluctant members of the British government were willing to give coup plotters what they had been looking for—clear and forceful opposition to Hitler as head of the German state and his saber-rattling threats in Eastern and Western Europe and permission to depose him.

On March 11, 1940, the British government said it would discuss terms of peace with Germany if Hitler was removed from power and the rule of law was reinstated. (John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 85) The problem for the conspirators this time? Getting their own military leaders to give the order that would set in motions the coup that would oust Adolf Hitler.

Start of the Phony War

Despite the Munich accord, Allied governments as well as German military leaders could do little to stop Hitler from pursuing his plan for a new German empire. Hitler defied the Munich agreement’s protections of Czech independence months after it was signed—under the threat that Prague would be leveled by German bombers, Czech troops surrendered to the German Army and the country was absorbed by Germany as the Protektorate of Bohemia and Moravia on March 16, 1939.

Soon after, German troops occupied Memelland in Lithuania, a trade treaty brought Romania under German control, and Hitler signed non-aggression agreements with Latvia, Estonia, and Denmark. He allied himself with Mussolini through the Pact of Steel in May, 1939, and Stalin in August, then ordered troops to invade Poland on September 1.

Although both France and Britain immediately declared war against Germany, neither country was firing shots. French forces quickly withdrew after a minor assault on German territory soon after the Polish invasion, and Britain only went so far as to mobilize the Royal Navy to block German ports. (James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler)

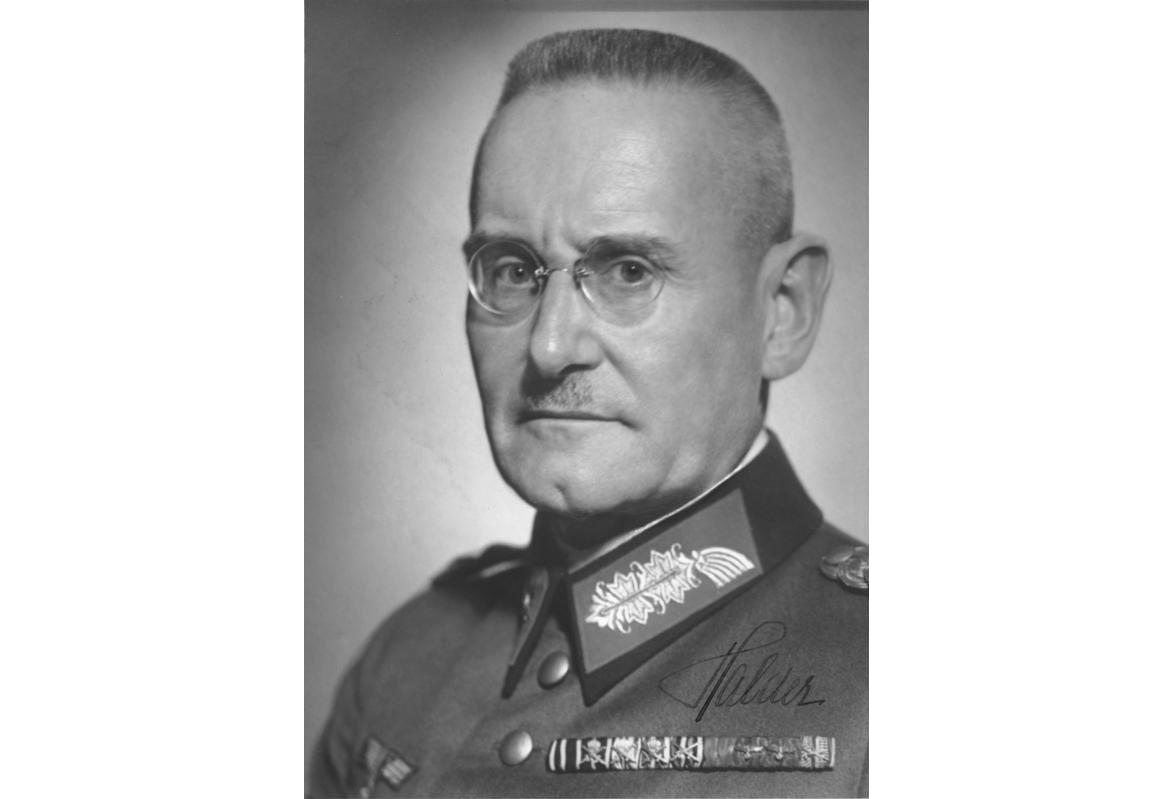

Franz Halder. https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/franz-halder/

The German military argued futilely against preparations for aggression against the west or further action in the east. In November, 1939, General Franz Halder noted that the army was not prepared for an offensive—there were not enough officers to lead troop movements, personnel in some units had not been adequately trained, materiel was in short supply and took days to resupply, and some divisions were understaffed by at least a third. Though none of the members of army headquarters believed an offensive had “any prospect of success,” Halder wrote, “any sober discussion of these things is impossible with [Hitler].” (Charles Burdick and Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: The Halder War Diary)

The German Resistance

Though Oster conspirators had torn and set fire to their coup plan notes and maps days after the Munich accord, they had not fully given up. Members of the German Resistance became liaisons between groups opposed to Hitler within various branches of the civilian government and the military, got union leaders to promise they would strike against the government in support of a coup, and encouraged individuals who considered quick hits against Hitler—eg, invitations for Hitler to inspect fortifications where a grenade would be detonated or where other measures would be taken to “render him harmless once and for all.” (Target, p 89)

Coup planners decided to resurrect the hand-written plans Oster had secreted in his safe in 1938 and once again approach the British government for support. Coup planners had hoped in vain for Britain to make clear to the German people that a coup was necessary to stop Hitler from triggering a shooting war in 1938. This time, they wanted to be sure neither Britain nor France would take advantage of any turmoil following a coup and invade Germany.

Emissaries to Great Britain, including Pope Pius XII, eventually convinced Lord Halifax, and Prime Minister Chamberlain acceded to plotters’ demand that the country would not invade if they succeeded in their attempt to assassinate the head of the German government. Specifically, the British government on March 11, 1940, agreed it would discuss peace with Germany as long as Hitler was no longer head of state, the country adhered to the rule of law, Poland would be liberated, the territories that had recently come under German rule could decide their fate for themselves, Germany would not wage war in western Europe, and an armistice would be negotiated via the pope. (The Hitler Assassination Attempts)

Britain’s acquiescence with the coup planners did not come without complaint. As Francis D’Arcy Osborne, British ambassador to the Holy See, noted: “If they wanted a change of government, why didn’t they get on with it.” (The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 84)

A New Coup

Two leaders of the German Army were critical for setting a coup attempt in motion. Army Chief of Staff Franz Halder was needed to sign off on operational details that would lead to the assassination of Adolf Hitler and the creation of an interim government. His superior, Army Commander in Chief Walther von Brauchitsch, was the man who could issue the order to move against the Nazi leader.

In September, 1939, while Hitler was pushing for an invasion of western countries, Halder and Brauchitsch felt they had only three options—to follow Hitler’s orders for what they considered to be a disastrous military assault, do whatever they could to delay the mission, or work for “fundamental change.” (Joachim Fest: Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 121)

Hitler’s insistence on a military campaign with an aggressive timeline—a full-blown attack within months—led members of the general staff, military intelligence, a Resistance cell within the high command called Action Group Zossen, and the foreign office to push Halder and Brauchitsch for coup marching orders. Yet the men hesitated. Halder worried that no one was prepared to take Hitler’s place as head of the government and that younger officers were not ready for a putsch. An offhand remark from Hitler about “the spirit of Zossen” made Halder believe coup plotters may have been betrayed or the plan uncovered, and there was infighting among the plotters. “If they’re so sure at Military Intelligence that they want an assassination, let [them] take care of it…,” Halder complained. (Plotting Hitler’s Death, p 134)

The Oster conspirators nevertheless regrouped in early 1940 after Britain’s peace proposal in March. In a repeat of the 1938 coup plan, key locations within Berlin were identified, operatives were prepared to occupy the locations and seize resisters to the coup, impose martial law, and notify the public that elections would be held soon and peace talks would begin with Allies. (The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 85)

Franz Halder and Walther von Brauchitsch

But Halder and Brauchitsch stood down. Halder no longer felt Hitler’s plans for aggression were doomed for failure. He had reviewed troop strength on the west and in Poland and found they had been expanded and refitted and troop divisions could triple in size in months, factories were producing aircraft, guns, and tanks, and the recalcitrance of the British and the French was giving Hitler the time he needed to mount a superior force. (Herbert Malloy Mason, Jr: To Kill the Devil, p 93) A humiliating and costly military defeat was no longer assured.

And Brauchitsch faced reality: Action taken against the head of government while the country was at war would not only would be treasonous, a coup was bound to fail. As Brauchitsch said after the war: “Of course, I could have had Hitler arrested and even imprisoned him. Easily. I had enough officers loyal to me who would have carried out even that order if given by me. But that was not the problem. Why should I have initiated action against Hitler…? It would have been action against the German people. The German people were pro-Hitler.” (The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 86.

Sources:

John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, Frontline Books, 2022.

Joachim Fest: Plotting Hitler’s Death, Henry Holt and Company, 1997.

Herbert Molloy Mason, Jr. To Kill the Devil, W. W. Norton and Company, 1978.

James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler, Praeger, 1992.

Charles Burdick and Hans –Adolf Jacobsen, eds: The Halder War Diary, Presidio, 1988.