Then & Now

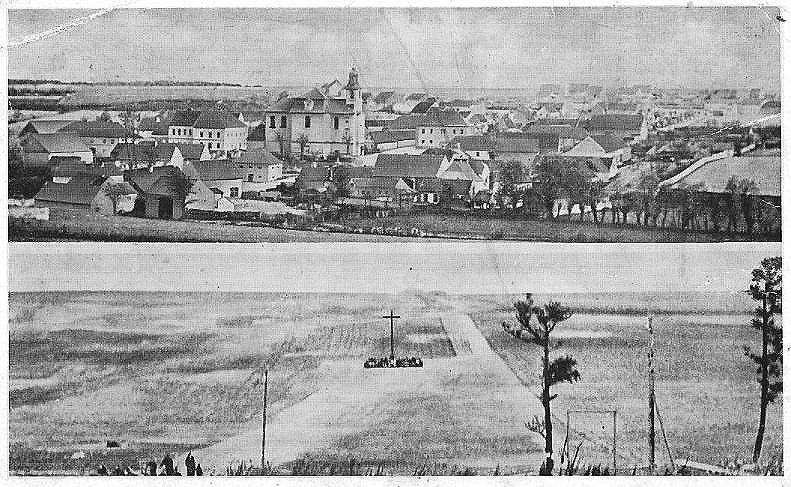

Lidice in 1942 and 1945

The small town of Lidice is shown at the top of the picture before it was targeted for destruction by the Nazi high command in 1942 in retribution for the assassination of the head of Nazi-Occupied Czechoslovakia Reinhard Heydrich. At the bottom of the picture is the memorial to the town that was created in 1945 by the Soviet Red Army. The memorial rests on the site of the mass burial of the town’s men, killed by a Nazi firing squad on June 10, 1942.

The Lidice Commemorative Ceremony 1945

A commemorative event was held in 1945 on the site where Lidice once stood. More than 100,000 people attended the ceremony, including some of the women of the town who survived the attack and imprisonment at one of the Nazi’s forced labor camps. A video recording of the commemorative services may be viewed on YouTube.

Excerpt from The Pear Tree:

“Milan?” Chessie gingerly touched his shoulder. “Could I talk to you? It’s Chessie,” she said as she sat down next to him. “Remember when you and I were in the DP camp?”

He turned his head toward the sound of her voice and squinted his bloodshot eyes.

“I wanted to talk to you about this place …” She pulled out a copy of the Svobodné Slovo and pointed to an article circled in pen. “It’s a memorial site at Lidice. A priest told me about it. The story is about the ceremony that was held—it was in June.”

Her fingers rested on a photograph that captured Czech President Edvard Beneš as he walked past a row of five flagpoles, their banners at half-staff. In front of him stood a tall metal cross, a ring of twisted metal binding the two bars together. The cross stood behind rows of evergreen trees, one tree for each man killed by the Nazis almost exactly three years ago to the day. A second photograph showed a crowd of thousands, along with hundreds of wreaths and other floral displays and an urn with a perpetual flame, its smoke wafting in the breeze. More than 100,000 Czech citizens had made the pilgrimage, walking or biking to the valley where the city once stood, the newspaper article reported. The people had watched a procession of Czech and Soviet soldiers, schoolchildren in regional folk costumes and dignitaries march across a raised earthen bridge over Lidice creek, then listened to a military band and finally stood in silence as the monument was dedicated.

“The priest told me that Beneš, the president, before he even went to the memorial site—he vowed that no one would forget what happened … to our town. The ceremony and the cross and the trees,” she stroked the photograph. “Are meant to create a sacred place … to honor …” She coughed as the emotion rose in her throat, paused and then lifted her head. “It’s meant for us, Milan. It’s a place for us to …”

“To what?” Milan circled the rim of his beer mug with a finger. “Nothing is there, you know. I went—” he slapped the photographs. “After Kladno. I saw …” He wrapped his fingers around the heavy glass. “Nothing … is there.”

“We could go there—say goodbye. I could say goodbye to my son. Even if he is not buried there. He lived there once. His memory is there. And … you … could …”

“What do I care about that? That place—where the town was—is dead.”

“I don’t believe that, Milan. Yes, many have died, most in our town have died. But there is also life. Parts of our town are alive, there at the memorial site. Others from our town are alive—somewhere—they’re just lost. They’re living … somewhere … away from us … loving us as we love them, even if we will never know where they are.

“We could find peace, Milan.”

“Peace?” he said harshly. “And just how is that going to happen?” He stared at her. “My mother is gone. No one can tell me where she was taken, what happened to her. No silly memorial …,” he waved at the newspaper, “… is going to change that.”

“But, Milan …” Chessie said, lightly touching his arm.

He shrugged off her hand as he raised the mug to his lips.

“What’s happened to you, Milan?” Chessie tried again to touch him, but he rose, stumbled against the table leg, walked to the bar and slid the mug toward the bartender. She watched him as she folded the newspaper and put it into her pocketbook. She started to follow him to the bar, but then thought better of it and left the tavern.

The Men’s Tomb

The original memorial to Lidice built by the Soviet Red Army in 1945 placed a tall metal cross in the midst of a stand of trees, each one planted in memory of a man executed by Nazi riflemen on June 10, 1942. The cross and the trees remain today, erected on top of the mass grave where the men’s bodies were buried. The Men’s Tomb is one of several commemorative areas within the Lidice Memorial, located on what once was the actual site of the village of Lidice, 12 miles northwest of Prague.

Excerpt from The Pear Tree:

Chessie was surprised to see that Milan had come onto the memorial grounds and was standing next to the rows of evergreens above the mass grave that held the bodies of the men of Lidice. Moving next to him, she let her shoulder touch his.

“It’s so hard,” he said, without turning toward her. “The men, the boys, Ceslav are …” He pointed down. He paused. “She’s dead, isn’t she?” He looked at Chessie.

“I believe so, Milan.”

“She’s dead. My mother … and I’ll never …” He stopped, his words strangling his throat, burning his lungs as they gave testimony to the reality he had tried so hard to disprove. He raised his head, threw it back and opened his mouth. With all the force of his being, he howled. He converted all the pain of loss and guilt and failure into a sound, raw and feral, that gave voice to his thoughts and feelings when his mother had collapsed at the sight of his dead brother, when she folded into herself and couldn’t respond to his touch, when he took her limp, insensate arm in his and fended off Kleinschmidt’s blows, when he woke to find himself alone on the gymnasium floor and his mother gone. It captured his feelings when he returned to Lidice and stumbled on the grave of his pet—the only clear sign of the town where he and his mother and family had lived and loved. The sound reverberated throughout his body, making his chest heave, his arms twitch, his shoulders shudder.

At last he dropped his head to his chest and gave in to the sorrow as it rose from his core and culminated in rapid, convulsive breaths. “Help me,” he whispered as Chessie wrapped her arms around him. He let her hold on to him until the shaking stopped.

Foundations from Original Lidice Buildings

Ten years after the creation of the original memorial by the Soviets, remnants of the town were preserved, including the foundations of the town schoolhouse and church and Horak’s farm, where the men of Lidice were lined up against the farmhouse wall and executed by firing squad. Memorial and Reverent Area

Today’s Lidice Memorial rests on the site where the Soviet Union’s Red Army soldiers erected the original memorial in 1945. The first museum was built in 1952. It was replaced by a new museum ten years later on the 20th anniversary of the destruction of the town.

A garden of peace, with 29,000 rose plants donated by 32 countries around the world, was opened in 1955 and renovated in 2003.

The Foundation of the Horak Farm Today

The Horak Farm 1942

Excerpt from The Pear Tree:

SS Obersturmbahnfurer Max Rostock led his men under the arch of the brick and stone entry gate and into the courtyard at Number 13, the Horák farm. Several meters from the main house, he started dividing the men into two lines. He stationed the first group so the men stood directly in front of a row of mattresses that had been propped against or laid on the ground in front of the farmhouse wall. He arranged the second group a few steps behind and to the right of the first.

Each of the men in the first of Rostock’s two groups released his rifle from its shoulder harness and let the weapon lean against his leg. The men relaxed, bouncing up and down to release the tension. Each of the men in the second group dropped down to his knees and removed a series of cartons from his canvas pack. The men pried open the lids from boxes of ammunition and began freeing rounds from their packaging.

Rostock paraded slowly up and down the rows of men, stopping occasionally to adjust a helmet or smooth a lapel. Satisfied that his men were presentable, he stepped aside and made room for his superior officer, SS Hauptsturmfürher Harald Wiesmann. Wiesmann ran a critical eye over Rostock, the farmhouse, the rows of Sturmmann. He nodded curtly to Rostock, then positioned himself in front of the men. “It is the will of the Führer,” Wiesmann made sure they understood, “which you are about to execute.”

SS Sgt. Engel guided the truck past the city proper and entered the Lidice farming area, passing Number 11 with its fields of sprouting beans and Number 12 with its rows of squash. At Number 13, he stopped in front of a stone archway, a linden tree to one side, its branches slanting across one of the columns.

“You stay here,” Engel told the corporal as he opened the driver’s side door and stepped onto the running board. “Not that they’re …,” he indicated the passengers huddled on the bed of the truck, “going anywhere, but still …”

Engle walked into the courtyard in front of the farm buildings and past the stable, pausing when he heard voices inside the walls. Men’s voices. A lot of men’s voices. He turned the corner of the building and entered the yard, where an Obersturmführer and a Hauptsturmfürher were eyeing the policemen, straightening out the rows, swatting at sagging buttocks or slouching shoulders. “Herr Obersturmführer Rostock?” Engel approached the officer warily.

“What?” Rostock barked.

“Engel. From Terezín.” He saluted the Obersturmführer.

“Well, it’s about time,” Rostock appraised Engel, tightening the collar of his uniform.

“We had—”

“I don’t want to hear it,” Rostock silenced Engel. “I need you to get those men started.”

Rostock led Engel to a garden area on the other side of the farmhouse. “There,” he indicated a spot between walnut trees and pines, next to mulberry bushes and sprouting spring vegetables. “I need a plot 20 by 30 meters, 10 meters deep.”

“That will take all day.”

“It will take all day before we can start filling it.”

The Children’s War Victims Monument

Several sculptures have been added to the grounds over the years. One of the most prominent is the Children’s War Victims Monument. A professor of sculpture Marie Uchytilová created a bronze monument for Lidice children who died in gas vans in Chelmno as well as other children killed in war. The monument consists of 82 larger-than-life-size statutes that took Uchytilová more than two decades to complete. The sculptor finished a plaster version of the artwork before she died in 1989. Her husband, J. V. Hampl, continued the work. Hampl completed 30 bronze statues in 1995 and continued to add more statutes until 2000, when the last seven were installed. The Children’s War Victims Monument today features 42 girls and 40 boys looking over the Lidice Valley, in remembrance of those who died in 1942. The first of the statues of the monument were placed in 1995, and the full monument was completed in 2000.

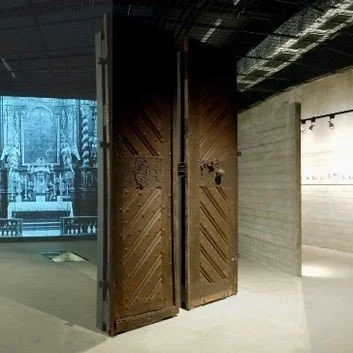

The Museum

The first museum on the Lidice Memorial site was opened in the early 1950s. In 1962 on the 20th anniversary of the Lidice tragedy, a new museum built according to a plan by architect František Marek opened. Major reconstruction of the Marek museum began in 2005, and on the 64th anniversary of the Lidice village massacre in 2006, the renovated museum opened.

Highlighting this opening was the introduction of a permanent, multimedia audiovisual exposition called And Those Innocent Were Guilty. This exhibition superimposes projections of authentic, archival photographs from the Lidice repository and scenes filmed in the style of family movies on plain concrete walls to inform visitors about the life and destiny of the village inhabitants, the town’s destruction and renewal, and background on the key events that occurred at that time. Museum - Lidice Memorial (lidice-memorial.cz)

Today’s Lidice Memorial

The modern era of the Lidice Memorial began in 2001 when the Czech Ministry of Culture established a benefit organization to restore and preserve the grounds and buildings as a National Cultural Heritage site. In addition to renovations of the Rose Garden, the Lidice Gallery that houses an art collection dedicated to the memory of the town, the International Children’s Art Exhibition, and the addition of a youth educational center and research room, work began on an exhibition celebrating a new Lidice.

The exhibition We Are Building a New Lidice is located in a one-family home built as part of the post-war restoration of Czechoslovakia in the 1950s and 1960s. The house replicates building and interior design of the post-war period, and it is furnished with original and restored furniture, most of which was donated by Lidice residents.

The Gallery

The Lidice Gallery is situated in the middle of the new Lidice village, approximately 500 meters from the premises of the Lidice Memorial museum. Originally it was built to a design of the architect František Marek as a community center. The construction works began in 1957. After 1989 it became a private property and stopped being used for its original purpose. The dilapidated building was taken over by the state and converted to its current use in 2002–2003.

The ground floor of the building has the permanent exhibition of the Lidice Collection made up of gifts to Lidice from artists from all over the world. The first floor holds regular short-term exhibitions while, from May to October, the marble hall on the 1st floor hosts the current edition of the International Children’s Exhibition of Fine Arts Lidice. The Lidice Gallery plays host to cultural events, concerts and theatrical performances.

The gallery space opens to the garden where cultural events are held in sunny weather and where some of the sculpted items of the Lidice Collection can be found.

Lidice Memorial - Organization of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (lidice-memorial.cz)

Books from the Lidice Memorial Book Shop

Brochure Lidice Before Lidice Today by Renata Hanzliková. Written in English, the brochure describes the fate of the village during WWII.

Lidice: The Story of a Czech Village, by Eduard Stehlik. Translated into English, this book is the first of its kind to present a full, detailed history of the village of Lidice in pictures and text both before and after the tragic events of WW II. This book was prepared for the Lidice Memorial.

Memories of Lidice, by Eduard Stehlik. This is the second book by historian Dr. Eduard Stehlik to chronicle the lives and times of the people of Lidice.

Building the New Lidice by Luba Hedlová, Pavla Becherová, and Martina Lehmannová. Written in both English and Czech, the book describes the building of the new village of Lidice after WW II and establishes Lidice as a symbol not only of tragedy but of hope for a new life.

Bridge of Hope and Life. Rose Garden of Peace and Friendship, Lidice 1955-2015, by Luba Hédlová, Přemysl Veverka, Jiří Žlebčík. Written in both English and Czech, the book chronicles the history of the Lidice Memorial Rose Garden.

Books - Lidice Memorial (lidice-memorial.cz)