Inside Men

As early as 1938, high-ranking members of the German military intelligence apparatus planned a coup that would remove Adolf Hitler from power. Driven initially by Nazi-generated scandals that forced out two top generals and actions that brought the military under Hitler’s direct control, the coup plan gained support and momentum when Hitler’s moves against Austria and Czechoslovakia threatened all-out war.

https://www.amazon.com/Oster-Conspiracy-1938-Military-Hitler/dp/0060955252

The Purge

On January 27, 1938, 59-year-old Werner von Blomberg resigned from his position as War Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces because of allegations about his new wife. Little more than two weeks before, Blomberg had married Margarethe Gruhn in a civil ceremony attended by Hitler himself and Luftwaffe Chief Hermann Göring. Under pressure from Hitler, Blomberg claimed he was retiring for “reasons of health” when in fact he sought to quash revelations about his wife’s criminal record for prostitution and a file of pornographic photographs, information obtained and passed along by Göring.

Army Commander-in-Chief General Barron Werner Freiherr von Fritsch was next. Hitler resurrected evidence of Fritsch’s homosexuality, evidence he had seen and rejected as wholly fabricated in 1936, and asked Göring to preside over a special court to investigate the charges. Fritsch resigned his post four days later on January 30, 1938.

On February 4, Hitler decided to “exercise personally the immediate command over the whole armed forces,” assuming Blomberg’s position as war minister, handpicking the successor to Fritsch’s position as commander-in-chief of the army, relieving 16 senior generals of their commands, and transferring 45 high-ranking officers, thereby replacing generals who were loath to go to war and reluctant to adhere to his will with “men of brutality,” men who thought the same way he did. (Roger Moorhouse: Killing Hitler)

Military Unrest

These sudden and shocking upper echelon changes built on disturbing undercurrents that were raising alarm among many of the German military.

Hitler had steadily enhanced the status of the armed forces by pointedly ignoring precepts of the Versailles Treaty that held the German military in check. Beginning in 1935, he enabled army expansion by allowing the reinstitution of conscription, remilitarized the Rhineland, blew past the limits that had been imposed by the treaty on the size of the military, increased funding and personnel, and modernized equipment. (Killing Hitler)

While many military leaders as well as the rank and file welcomed these moves, some were becoming concerned about the shift in the seat of their power.

Beginning on August 20, 1934, members of the armed services and civil servants were no longer required to take an oath to serve their country or its constitution. They now had to swear allegiance to a single man: to “render unconditional obedience to the Führer of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler…and be ready at any time to stake my life for this oath.” (Killing Hitler)

Military leaders who did not toe the line were put at risk. The Night of the Long Knives, which eliminated Ernst Röhm and most of the other Brownshirts (see the previous Historka post), also targeted General Kurt von Schleicher, chancellor of the Weimar Republic, who was gunned down in his villa near Potsdam, and his associate, head of the Abwehr military intelligence unit Ferdinand von Bredow for criticizing Hitler and his cabinet.

Most disturbing was Hitler’s push for war.

Run-up to War

On March 12, 1938, Hitler rode in one of a cavalcade of Mercedes automobiles across the German border into Austria as a “liberator,” making his homeland a province within the German Reich and absorbing its military into the Wehrmacht, thus violating one of the most uniformly despised clauses of the Versailles Treaty by Germans—Anschluss, unification of Austria and Germany.

A month later, Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht’s General Staff to formulate a plan for a preemptive attack on neighboring Czechoslovakia, the first step in his vision for a “German Empire which would include Poland, Ukraine, Baltic States, Scandinavia, Holland, Flemish Belgium, Luxembourg, Burgundy, Alsace-Lorraine, and Switzerland.” (Herbert Molloy Mason, Jr., To Kill the Devil)

The plan was considered to be disastrous for the country because of the status of Germany’s war machine—the military and defense industry were relatively weak and unprepared—the central location of the country, which opened it up to attacks on land, sea, and in the air, and the likelihood of provoking formidable enemies--Russia, France, Britain, and eventually the US.

Hitler nonetheless insisted: “It is my unalterable decision to smash Czechoslovakia in the near future.” (To Kill the Devil)

In the summer months, propaganda reported on the so-called atrocities committed by Czechs on Germans living in Sudetenland. The Sudeten Nazi Party led demonstrations and other actions in Sudetenland to disrupt the Czech government’s operations. Maneuvers were held in Franconia, near the Czech border, the infantry trained soldiers in methods of storming the type of fortifications maintained by Czechoslovakia, and throughout the country citizens were learning civil defense. (James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci , Target Hitler)

Preparations accelerated in September: tanks and infantry divisions practiced firing on concrete bunkers similar to the ones Czechoslovakia maintained on its border. Concrete “dragon’s teeth” were being constructed, tank traps were being dug, and machine guns were being mounted along German’s West Wall or the Siegfried Line.

Hitler set the deadline for an attack on Czechoslovakia—no later than October 2. (John Grehan, Assassination Attempts)

The Men

Key Plotters

Abwehr’s organized effort to remove Adolf Hitler from leadership was called The Oster Plan or the Oster Conspiracy. (See the next Historka for details.) Several men in- and outside the military were instrumental:

https://alchetron.com/Hans-Oster

Colonel Hans Oster, Abwehr officer, was openly contemptuous of the Nazi Party, telling an Austrian officer who began to raise his arm: “Oh, no, no Hitler salute here.” (To Kill the Devil, p 34). He was the linchpin, the man who fostered communications among the conspirators.

General Ludwig Beck, chief of the General Staff, who considered the time he had to take the new oath of allegiance to Hitler the blackest day of his life. (To Kill the Devil, p 35). He was the link to high-ranking members of the Wehrmacht.

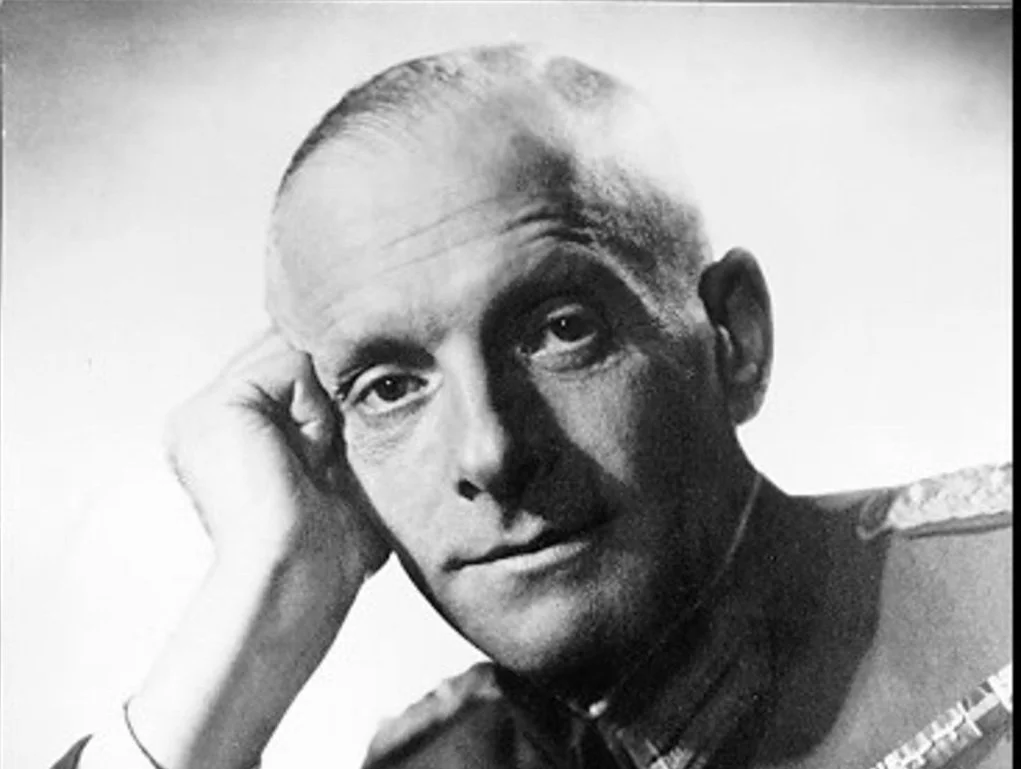

https://alchetron.com/Wilhelm-Canaris

Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, viewed Nazis as no more than a gang of criminals. He began looking for ways to use the intelligence agency to bring Hitler down soon after he was appointed its chief of operations.

Hans Bernd Gisevius, police liaison to the Abwehr and former member of the Gestapo. He was central to the success of any action taken against Hitler by gaining the support of local police.

https://alchetron.com/Franz-Halder

General Franz Halder, head of the General Staff, believed Hitler was not only a criminal but a “sexual psychopath” and “bloodsucker.” He replaced Beck after his resignation from the General Staff in September, 1938, and communicated regularly with plotters within the ranks of the military as well as civilians, including Giesvius.

Others

General Erwin von Witzleben, commander of Berlin’s military district, supported Gisevius, providing a private office next to his own at headquarters as well as false identity papers, and spearheaded the recruitment of commandos who would storm the Reich Chancellery, arrest Hitler, and transport him to a castle in Bavaria.

Lieutenant Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz, Abwehr staff, recruited and trained 60 men to act as commandos, as per Witzleben’s order.

General Walter von Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt, commander of the Potsdam garrison, mapped out locations within Berlin that needed to be quickly taken over by troops at the outset of the coup: the radio transmitter, Gestapo headquarters, and the Chancellery itself as well as escape routes.

Carl Friedrich Goerdler, mayor of Leipzig, obtained funds from industrialist Robert Bosch to finance travels to Britain and France where he met with government leaders and tried to get their support for regime change within Germany.

General Erich Hoepner, commander of the Wuppertal Panzer Division, planned to have tanks and armored vehicles on alert and ready to contain any armed response to the coup.

Theodore Kordt, counselor from the German embassy in London, and landowner Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin warned the British government about Hitler’s plans for war and sought support for the Oster coup.

Hjalmar Schact, director of the Reichsbank, provided economic and other data warning against Hitler’s plan to invade Czechoslovakia and supporting the coup attempt and communicated regularly with fellow conspirators Goerdler and Gisevius.

Sources:

John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, Frontline Books, 2022.

James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler, Praeger Publishers, 1992.

Herbert Molloy Mason, Jr.: To Kill the Devil, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1978.r

Roger Moorhouse: Killing Hitler, Bantam Books, 2006.