The Lone Wolf

Adolf Hitler traveled to Munich on November 8, 1939, to give the speech that commemorated the Beer Hall Putsch. He had been giving a speech on that date for the last six years to remind followers of the Nazis’ audacious attempt to overthrow the Weimar Republic in 1923 and reiterate his declaration at the time that the “National Revolution” had begun.

This year he had to improvise, however. Instead of starting the speech at 8:00 pm and ending two hours later as was customary, he began an hour earlier and ended after 60 minutes. He needed to return to Berlin that same night to finalize plans for a western offensive and heavy fog prevented a quick night flight.

Standing at the podium in front of a pillar bearing the red, black, and white swastika flags in the Bürgerbäukeller, Hitler railed against the British: “When has there ever been a people more vilely lied to and tricked than the German Volk by English statesmen in the past two decades?” And he exhorted his followers to action: “This is a great time. And in it, we shall prove ourselves all the more as fighters.” (Killing Hitler, p 64-5)

He then left the beer hall at 9:07 pm.

Thirteen minutes later, a bright light flashed, a blast roared, and a rush of air toppled tables and chairs, shattered windows, and blew out doors. The podium and pillar exploded, the dais and lectern crumpled, the ceiling crashed to the floor, and more than 50 of the men who had stayed behind were injured or dead. (Killing Hitler, p 66)

The target of the attack learned about the incident minutes later when his train stopped in Nuremburg. At about the same time, the perpetrator approached the Swiss border. He was stopped by German guards and turned over to the Gestapo almost immediately when a postcard of the Bürgerbäukeller, sketches of a bomb, and a fuse were found in his pockets.

Five days later, the man confessed. He was Georg Elser, an ordinary German, a member of the working class expected to be a staunch supporter of the Nazi Party. Even more surprising, he had acted alone, meticulously and patiently putting the incendiary device together.

The Plan

Elser decided almost immediately that the beer hall would be the location for his assassination attempt. The speech came off every year at the same location like clockwork. The streets outside the beer hall were routinely barricaded, crowded, and afforded little chance of a good shot. And the beer hall itself was fairly easily accessible. When he visited in November, 1938, Elser noticed that the speaker’s platform was in front of a column supporting the upper gallery of the building and in the middle of the hall. “In the course of the next few weeks,” he reported in his confession, “I slowly worked it out in my head that it would be best to pack explosives into this particular pillar behind the speaker’s platform and then by means of some kind of device cause the explosives to ignite at the right time.” (Bombing Hitler, p 157)

The Bomb

Since the summer of 1937, Elser had been working at the Waldenmaier armaments factory. Because of lax security, he was able to gather 250 compressed pellets of explosive powder, secreting each of the discs in sheets of paper and covering them with clothes in his locker. Realizing he needed more explosives as well as details about fashioning a detonator, he got a job at the Vollmer quarry in Itzelberg. Elser was able to pick up cans of explosives that had been left behind after blasts and “pay a visit” to the hut that served as a supply depot, easily filing down a key to fit the lock on the iron exterior door and yank open the unlocked wooden interior door. (Bombing Hitler, p 161, To Kill the Devil)

Elser trailed explosives experts at the quarry to learn their techniques and tested four devices in his parent’s orchard in the summer of 1939. The devices consisted of three blocks of explosives mounted on a board with a spring stretched across, a rifle shell as a firing cap, and a nail as the firing pin. He placed the materials, including 110 pounds of explosives, 125 high-capacity detonators, and quick-burning fuse, in the false bottom of his wooden suitcase and carried it with him when he moved to Munich in August, 1939. (To Kill the Devil)

The Placement

Elser began having dinner in the Bürgerbäukeller regularly. He sat at the same table served by the same waitress a little after 8:00 pm. He ate the cheapest meal, had a single beer, and left the table about 10:00 pm. He canvassed the hall by walking through the cloakroom. When he was sure no one was watching, he climbed the stairs to the gallery and hid in a storage space behind a folding screen.

Elser waited for the sound of the key turning in the lock between 10:30 and 11:30 pm, then quietly made his way along the gallery to the column that would be the backstop for Hitler’s speech on November 8. He first created a door close to the bottom of the column, then he chiseled out a chamber for the bomb using a hand drill with a chisel bit. He covered his tools with rags to minimize the noise and stopped making loud actions, such as chipping out portions of brick or masonry, until sounds from outdoors could camouflage them. He worked for several hours each night, then dozed until morning when he walked out of the beer hall soon after it opened between 7:00 and 8:00 am.

He spent three to four hours a night over the course of about a month to hollow out the pillar, insert the bomb, and set the timing device, each time sweeping up dust and debris, hiding the detritus in a storage room on the gallery until he could return with a suitcase to remove any signs of his work. He loaded explosives, made corrections to his ignition device, added wire and started the clock on November 5, setting the timer to detonate the charge 63 hours and 20 minutes later. (Bombing Hitler, To Kill the Devil)

The Man

Elser was born in January, 1903, in a small village in southwest Germany, a region known for the manufacture and sale of cuckoo clocks. After working briefly for his father, he apprenticed as a lathe operator in a smelter at age 14 and soon left because of health issues. He switched to woodworking, graduating at the top of his class from the Heidenheim trade school eight years later. He then worked in a furniture factory, a factory that made aircraft propellers, and as a carpenter building desks. He also worked for a brief time at a clock factory.

Georg Elser: Seine Bombe gegen Hitler explodierte pünktlich – 13 Minuten zu spät - WELT

Though not part of any organized political movement, Elser was driven to take action against Hitler because of National Socialism’s failure to improve the lot of the ordinary German worker. The German economy had improved with the rise of the Nazis. Workers’ wages had dropped, however, from 1 mark an hour in 1929 to 68 pfennigs in 1938. At the same time, withholding taxes doubled from 10 to 20 percent. (To Kill the Devil) “The workers find themselves under constraint,” he wrote. “Under the new laws, for example, they cannot change the place where they work; they cannot move to another town to look for a better job. No that is forbidden.” (To Kill the Devil, p 91)

Another driving force was the fear of war and the need to take action to avoid it. He stressed that “the dissatisfaction among the workers that I had observed since 1933 and the war that I had seen as inevitable since the fall of 1938 occupied my thoughts constantly… On my own, I began to contemplate how one could improve the conditions of the working class and avoid war.” His conclusion—to remove the leadership of the country, including Hitler, Göring, and Goebbels. “I came to the conclusion that by removing these three men other men would come to power who would not make unacceptable demands of foreign countries, ‘who would not want to involve another country,’ and who would be concerned about improving social conditions for the workers.” (Bombing Hitler, p 151)

After his arrest, Elser was taken to the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen where he was beaten repeatedly and severely and drugged. In early 1945 he was taken to the camp at Dachau. Days after Hitler’s suicide, Elser was killed by a pistol shot to the back of the head.

Conspiracy Theories

Although evidence is clear that Elser acted alone, German leadership and the press believed otherwise. Among those blamed were the Nazi-opposition group organized by Otto Strasser—the Black Front—British SIS, and even Heinrich Himmler himself. Strasser, publisher of the Nationaler Sozialist, wrote in November, 1939, that he had “definite proof from a very reliable party member [that] the plot was the idea of Himmler himself, who told Hitler’s deputy Rudolph Hess that he needed an attempt on Hitler to let loose a hate offensive against the British and in order to have a pretext to attack internal enemies.” (The Hitler Assassination Attempts, p 99)

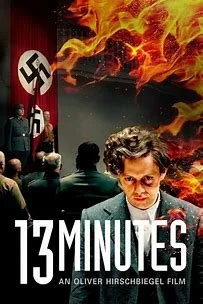

Essays and articles appearing in the 1960s and ‘70s confirmed Elser’s status as a lone wolf. A film by Klaus Maria Brandauer in 1989 made Elser and his actions well known across Germany. Most recently, the film 13 Minutes brings the man and his actions to life.

Sources:

Bombing Hitler, Hellmut G. Haasis, Skyhorse Publishing, 2013.

Killing Hitler, Roger Moorhouse, Bantam Books, 2006.

The Hitler Assassination Attempts, John Grehan, Frontline Books, 2022.

To Kill the Devil, Herbert Molloy Mason, Jr., W. W. Norton & Company, 1978.