Caught in the Act

Threats against the life of the new German Chancellor, Adolf Hitler, were not unusual. In the months after he became head of parliament, police received tips about possible assassination attempts at least once a week. (Peter Hoffman: Hitler’s Personal Security) Some were fabricated by Heinrich Himmler who was jockeying for position in the new Reich in February and March of 1933. Some were far-fetched: one would-be assassin supposedly planned to squirt poison into Hitler’s face from a bouquet of flowers, another hoped to rig a fountain pen with an explosive that would detonate in Hitler’s hand (Hoffman: Hitler’s Personal Security, page 24-25).

Others were either pranks or mistakes. A telephone call to police on the day before the Prussian State Council was scheduled to meet warned of a time bomb hidden in the coal cellar of the ministry building. A suspicious object on the cellar stairs turned out, however, to be container of packing cord left behind by workers who had maintained the building years before. (Hoffman: Hitler’s Personal Security, page 25)

A couple of incidents may have been flat-out bravado or the result of wishful thinking. Two plotters offered information about assassination plans to officials in the United States. One, in exchange for cash. In October, 1933, a man identifying himself as M. X. Kimball approached the German embassies in Chicago and Washington, D.C., and asked for money to reveal the details of a plot by American Jews to send an emissary to Germany who would kill Hitler. According to the plan, a man of Jewish extraction would travel to London where he would get information about how to meet with Hitler in his office where the murder would be committed. (John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts)

A few months earlier, another man, Daniel Stern, wrote the German Ambassador in Washington, stating he would travel to Europe and assassinate Hitler if President Roosevelt did not demand an end to the persecution of Jews in Germany. A nationwide search could find not find Stern or any links to him. (Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, page 25-26)

But many of the threats real enough to be investigated were thwarted before they got very far.

The Potsdam Day Bomb Threats

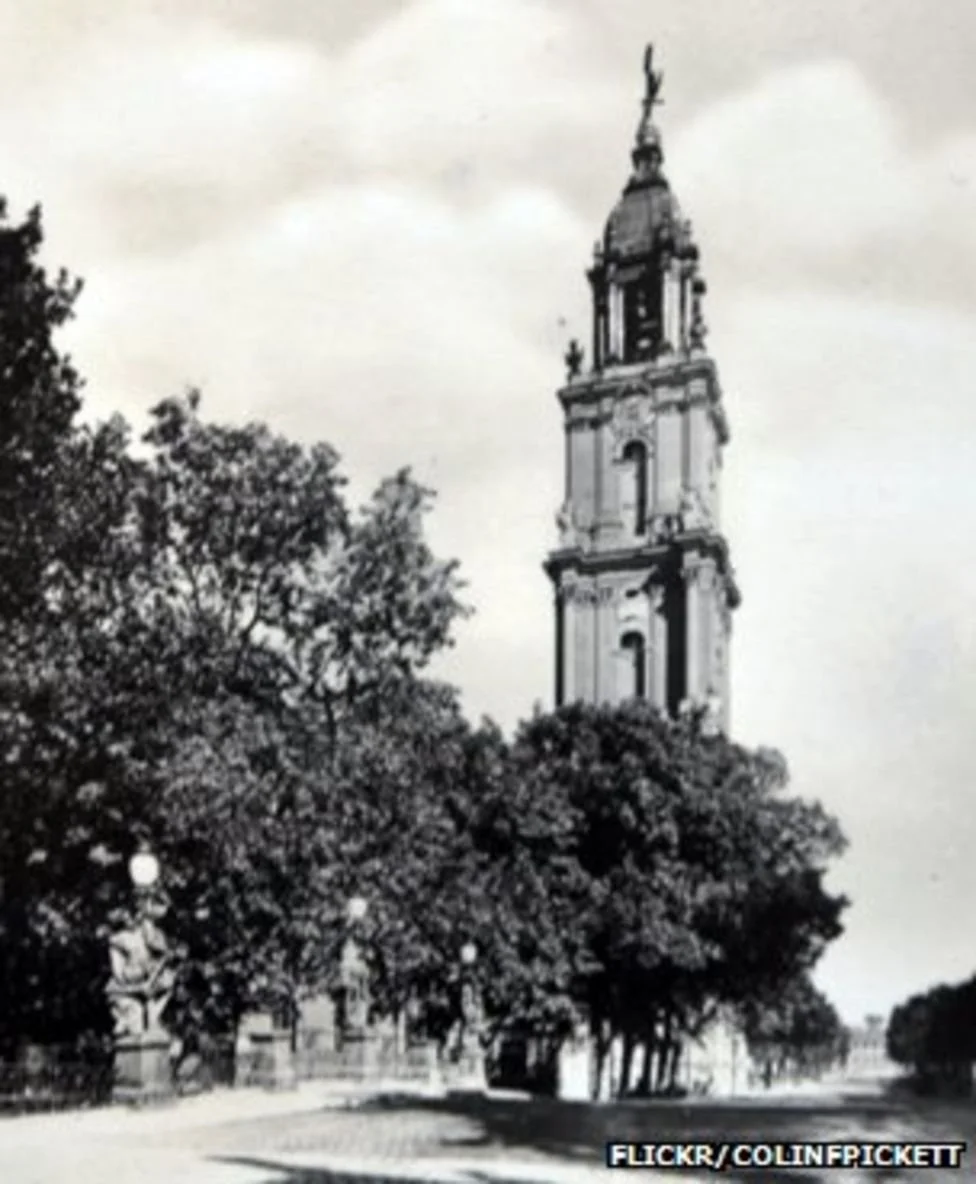

A tip from an unlikely source--a medium who obtained messages via a crystal ball--reported that a tunnel had been dug under the Potsdam Garrison Church where Hitler was scheduled to symbolize the “marriage of the old grandeur with new power” through a formal handshake with the president of the German Reich, Paul von Hindenburg, during the celebration of the reopening of the Reichstag on March 21, 1933. (An arson attack burned the original Reichstag to the ground a month before. This fire was used by Hitler as a pretext to accuse Communists of attempting to overthrow the German government and led to the Reichstag Fire Decree that suspended civil liberties throughout Germany.)

The church described as a 'symbol of evil' - BBC News

Before the newly elected members of the Reichstag would reconvene in Kroll Opera House, Berlin, Hitler and Joseph Goebbels organized speeches, religious services, parades, and memorials in an event known as Potsdam Day. The city of Potsdam was selected for the ceremony because it had been the seat of Frederick the Great’s Prussian Kingdom as well as Otto von Bismarck’s German Empire. The date was chosen because Imperial Germany’s first Reichstag opened on March 21, 1871. In addition to Hitler and Hindenburg, dignitaries also included Crown Prince Wilhelm of the Hohenzollern dynasty and three of his brothers. (Potsdam Day-- Wikipedia)

Investigators did find that the tunnel “seen” by the medium was, indeed, being dug. But instead of being loaded with explosives, the tunnel was lined with cables so the Potsdam Day proceedings could be broadcast live over the radio. (Hoffmann: Hitler’s Personal Security, page 25)

Police intervened to eliminate two more serious bomb threats associated with Potsdam Day. The day before the event, Himmler reported that three Checkists had driven to the Richard Wagner memorial in Tiergartenstrasse, Munich, carrying bombs that would be set off as Hitler passed by on the way from the Potsdam festivities to the new Reichstag in Berlin. The men were spotted and arrested before they could plant and arm the devices, however. According to Himmler, “The authorities saw in every attempt of this kind the grave danger to public order and security. From his own knowledge of the public mood and from reports of subordinate officials, [Himmler] was convinced that the firing of the very first shot -- whether it hit the mark or not -- might lead to unequalled chaos throughout Germany and to a great programme which no power of the state or the police would be able to prevent.” (Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, page 25)

Days before Potsdam Day, Kurt Lutter, a ship’s carpenter and member of a small group of Communists, was arrested for planning to detonate the speaker’s platform while Hitler was addressing a political rally in Konigsberg on March 4, 1933. On March 3, a police informer who had infiltrated the group notified authorities, and Lutter and others were rounded up and interrogated. When none of the plotters owned up to the plan, they all were released. (Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts; James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler)

Tight Security vs. Loose Lips

Routine security measures foiled at least one potential assassin. Hitler regularly strolled up and down the hilly walking paths near his mountain retreat on the slopes of the Obersaltzberg mountain range, talking with compatriots as he crisscrossed over public hiking trails in the open countryside. Hitler’s bodyguards grew suspicious when they spotted a stranger in an SS uniform intently watching Hitler and his entourage. After stopping and searching the man, the security detail found a loaded gun and promptly arrested him. (James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler; Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts)

Informers sidelined other assassins. A school teacher in early 1933 told police that she had heard about a plan by Ludwig Assner, a member of the Bavarian State Parliament, to send a personal letter laced with poison to Hitler from France. On other occasions, Assner declared that he would not rest until he had shot Hitler or otherwise removed him from office. Assner’s plans were dismissed as extortion when he promised to desist if given a large sum of money. (Duffy and Ricci: Target; Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts).

An elaborate plan to infiltrate the SS and gather information about Hitler’s movements was itself infiltrated by Gestapo in 1935. Led by industrialist Dr. Helmut Mylius, head of the Party of the Radical Middle Class and editor of a right-wing political and economics publication, and the retired Navy Captain Hermann Ehrhardt, 160 Radical Middle Class Party men supporters actually were able to join the SS according to plan. But the size of the group may have been its undoing. According to John Grehan, such a large group made its discovery almost inevitable, as some members of the group most likely fell into the “loose lips” category. As a result, the plan was discovered, and most of the men were arrested. Mylius himself was able to circumvent arrest by joining the army, as arranged by his friend Field Marshall Erich von Manstein. (Duffy and Ricci: Target; Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts)

Plans by another potential assassin were foiled not once, but twice. Josef “Beppo” Römer in 1934 was arrested after gaining entry to the Reich Chancellery. A former member of the Freikorps paramilitary group who sought revenge for Hitler’s purge of the ranks of the SA on the Night of the Long Knives (June and July, 1934 when Nazi Party members purged SA from its ranks) and later a Communist, Römer was imprisoned for his actions at Dachau concentration camp. After his release in 1939, Römer again plotted to eliminate Hitler (or, as he said, “cut off the snake’s head”). He may have flagged his own actions, however, by dropping incriminating information about his analysis of German military action and active resistance into wastebaskets. (Grehan, page 34). Römer was arrested and sentenced to death in 1942 and executed in 1944.

A Cause Célèbre

The Stuttgart born and raised German Jew Helmut Hirsch was not able to enroll in a German university because of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. He therefore traveled to Prague and entered the German Institute of Technology there. He soon joined the Black Front, an organization of former members of the Nazi Party and German expatriates who opposed Hitler and led underground activities.

Helmut Hirsch Collection, Robert D. Farber University, Brandeis University

In December, 1936, he was sent to Nuremburg to meet a man who would give him two baggage claim tickets for suitcases containing explosives. He traveled to Stuttgart instead to meet a friend he hoped would talk him out of participating in the plan. When his friend did not arrive, he checked into a hotel across from the railway station. There, he was arrested by Gestapo the next morning.

Although he had no explosives in his possession, he was indicted for possessing them and conspiring to commit high treason and held in solitary confinement for nine weeks. At his trial, a Gestapo double agent described the plot in detail. But while Hirsch contended he should be acquitted because he did not travel to Nuremburg or acquire the suitcases containing the explosives, he did acknowledge that he would have, if given the chance, attempted to assassinate Hitler. He consequently was sentenced to death.

Hirsch’s family engaged international organizations in an attempt to commute the sentence to life imprisonment, including the International Red Cross, human rights groups, and Quakers. The case was appealed to the League of Nations and discussed in the British House of Commons. Because Hirsch’s father was an American citizen, Helmut was granted citizenship in the US in April, 1937. Despite efforts by the American ambassador in Berlin and Secretary of State, Hirsch was decapitated on June 4, 1937. (Helmut Hirsch Collection, Robert D. Farber University Archives, Brandeis University)

Sources

Peter Hoffman: Hitler’s Personal Security, DA Capo Press, 2000.

John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, Frontline Books, 2022.

Roger Moorhouse: Killing Hitler, Bantam Books, 2006.

James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci: Target Hitler, Praeger, 1992.

Garrison Church (Potsdam) Wikipedia.

Helmut Hirsch Collection. Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections, Brandeis University.