Shell Shock Recognition and Treatment

Though war trauma was described as long ago as 490 BC and has taken many names—battle fatigue in the 1940s, gross stress reaction in the 1950s, post-traumatic stress disorder since the 1980s—shell shock is inextricably linked to WW I, and not only because the term was first used in 1915 by psychologist Charles Myers. The condition has been indelibly experienced in novels about WWI—Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, Pat Barker’s Regeneration series, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun, Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, and more recently Steve Stahl’s Shell Shock and Ben Elton’s The First Casualty.

Shell shock is also a metaphor for the Great War, its apparent pointlessness, months-long stalemates trapping men in mud- and rat-filled trenches under barrages of exploding shells and clouds of poisonous gas while political leaders and military commanders ignored mounting casualties and rejected peace proposals for fear of losing strategic advantage. (Fiona Reid, Broken Men, David Stevenson, Cataclysm)

Clinical terms for unexplained disorders among fighting men likewise have a long, pre-WW I history: disordered action of the heart (DAH) or palpitations were described during the Crimean War and irritable heart during the Civil War. The entity known as shell shock resides within WW I, coined by the men on the battlefield who saw or felt it themselves. (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shell-shocked)

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/war_psychiatry

The Mystery

Shell shock was a puzzle. There was no single set of characteristic symptoms but a range of unexplained disabilities and sometimes contrasting symptoms: long-term bouts of insomnia and nightmares, generalized fatigue and jumpiness; pain in the chest as well as joints and muscles and cardiac palpitations; loss of function of an arm or leg, loss of voice, hearing, or other sensations. (Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely, Shell Shock to PTSD)

There was no apparent direct cause. An early theory linked symptoms with damage to the brain, hypothesizing that forces from a nearby explosion caused hemorrhages in the blood vessels of the brain and the release of carbon monoxide poisoned brain tissue. But many of the shell-shocked had never been close to an explosion, and some had not even seen combat. (Shell Shock to PTSD, p 23)

There also was suspicion. Some military leaders worried that the condition was used as an excuse by malingerers or cowards or caused by ingesting cordite or other drugs to quicken heart function and thereby avoid combat. (Shell Shock to PTSD)

The objectives of treatment conflicted as well. While some physicians sought to find a solution that would successfully treat shell shock, military leaders wanted quick action that would make soldiers well enough to return to the battlefield.

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/somme-offensive.html

Physical Treatment

As increasing numbers of infantrymen were felled by unusual symptoms, the British Expeditionary Force assigned Charles S. Myers, a medically trained psychologist, to study and try to decipher the cause of the unexplained phenomenon. His first cases exhibited similar symptoms—loss of the senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell as well as tremors, headaches, fatigue, and loss of balance. While the first three men had been near or affected by exploding shells, most later diagnosed as shell-shocked developed symptoms even if they were some distance away from explosions. ( https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-shock-of-war-55376701/#:~:text=The%20official%20Report%20of%20the,of%20concussion%20shock%2C%20following%20a)

Myers and his associate William MacDougal concluded that the condition was the result of repressed trauma, the body’s and mind’s efforts to manage the traumatic experience by repressing its memory and the resulting physical manifestations of the struggle to keep hiding that memory. (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shell-shocked

Myers’ plan for treatment built on that conclusion: “Myers and McDougall believed a patient could only be cured if his memory were revived and integrated within his consciousness, a process that might require a number of sessions.” Treatment therefore should be prompt, in a suitable environment, and psychotherapeutic. “Myers argued that the military should set up specialist units ‘as remote from the sounds of warfare as is compatible with the preservation of the ‘atmosphere' of the front.’ Myers and McDougall believed a patient could only be cured if his memory were revived and integrated within his consciousness, a process that might require a number of sessions.” (https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shell-shocked)

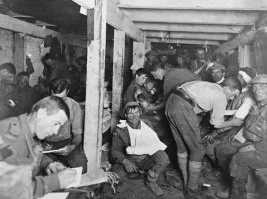

Not all forward units followed this treatment strategy, however. Several of the forward units, known as NYDN (not yet diagnosed nervous), relied on a regimen of rest, graduated exercises, route marches, with or without vigorous massage in an environment of respite and reassurance. American forward units added occupational therapy involving farming, road construction, and wood working and art therapy. (Shell Shock and PTSD)

Discipline also played a role. Both inside the military and outside in the overall British culture, “weak nerves” were shameful, especially during wartime, and the result of an individual’s lack of self-control and will power or outright fraud. The remedy? A personal commitment to recovery and the development of “nervous strength.” (Broken Men)

Faradism or electric shock therapy was one way to strengthen a weak will. Lewis Yealland, a Canadian neurologist, claimed to have removed the “hysterical disorders of warfare” by applying an electrical current to parts of the body. In his treatments at National Hospital for Paralysed and Epileptic, London, Yealland “bathed” patients in electricity by placing them on a wooden stool that was set on a platform with glass legs and charging them with static electricity (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electric_bath_(electrotherapy), using clamps or machines to mechanically force frozen limbs out of their static position, and apply other stimuli. To one patient, Yealland applied electricity to his neck and throat for periods of 20 minutes, lighted cigarettes to the man’s tongue, and hot plates to the back of his mouth. Treatment lasted four hours until the patient “was cured.” (Broken Men, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-shock-of-war-55376701/#:~:text=The%20official%20Report%20of%20the,of%20concussion%20shock%2C%20following%20a)

Psychological Therapy

A few forward shell shock treatment units followed the psychological approach of abreaction or talk therapy to release pent-up emotions (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abreaction). Psychological treatment was more commonly used in base hospitals in the UK, such as Craiglockhart Military Hospital in Slateford, and its physicians, including W. H. R. Rivers (profiled in Pat Barker’s Regeneration series).

Abreaction often began with hypnosis to guide shell-shocked soldiers into the past so they could recover memories and emotions associated with a traumatic event, and it followed a step-by-step process of reliving the traumatic event so it would no longer be suppressed but recognized and integrated into the conscious mind. (Shell Shock and PTSD)

Little apparently was learned about psychological therapy from the experiences of the shell-shocked and the doctors who treated them in WW I. The War Office Committee of Enquiry into Causation and Prevention of ‘Shell Shock,’ 1920-22 concluded that:

“In Forward Areas – No soldier should be allowed to think that loss of nervous or mental control provides an honourable avenue to escape from the battlefield, and every endeavour should be made to prevent slight cases leaving the battalion or divisional area, where treatment should be confined to provision of rest and comfort for those who need it and to heartening them for return to the front line.” (Extracts from a report from the War Office Committee of Enquiry into Causation and Prevention of `Shell-Shock’, (Catalogue ref: WO 32/4748)

The condition was not even discussed in post-WW I military training manuals, and many original military and medical treatment records were lost. The Blitz of WW II destroyed nearly 60 percent of British military records from WW I, and a fire at the National Personnel Records Office in St. Louis, MO, destroyed 80 percent of U.S. Army service records from 1912 to 1960. (Broken Men, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-shock-of-war-5376701/#:~:text=The%20official%20Report%20of%20the,of%20concussion%20shock%2C%20following%20a)

Remembering Shell Shock in Fiction

Some of the best known novels chronicling WW I include descriptions of the actual treatment of shell shock. The first in Pat Barker’s trilogy Regeneration (1993) takes readers into the treatment theater at Craiglockhart War Hospital and recreates psychotherapeutic sessions with Siegfried Sassoon by W. H. R. Rivers, the first military physician to advocate for cathartic abreaction, talk therapy to bring subconscious fears to the forefront, faced, and resolved.

Toni Morrison’s Sula (1973) looks at the other side of therapy—forcing the shell-shocked to overcome their shame and cowardice and exhibit proper behaviors through physical shocks, punishment, and discipline.

A couple of recent works reveal the chaos faced by frontline medical staff. Sisters of the Great War by Suzanne Feldman (2021) describes the “unexploded bombs, artillery noise, strafing planes, fire and damage from exploding shells, constant tension, wild rumors, dearth of necessary supplies, constant poor nutrition, lack of fresh water, and possible impending death” in hospitals and aid stations. (https://historicalnovelsociety.org/reviews/sisters-of-the-great-war/

The Shadow of the Mole details the “chamber pot of France” in the Argonne as Dr. Michel Denis makes his way to sickbay, walking in the trenches to the semi-underground medical way station located within crates of medical supplies, food, and ammunition as shells explode overhead, shake the walls, and flicker the light from candles in their lanterns. (https://historicalnovelsociety.org/reviews/the-shadow-of-the-mole/)

A psychological murder mystery links treatment of American vets from Iraq and Afghanistan to planned killings of Allied soldiers in psychiatric hospitals during WW I. (Shell Shock, 2024)

Both Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf and Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington illustrate the devastating consequences of ignoring or improperly treating shell shock (“suggesting an out-of-doors game” because there is “nothing seriously the matter”) and the importance of communication so the shell shocked and others can listen and learn.

Sources

Trevor Dodman: Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I, Cambridge University Press, 2015

Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely, Shell Shock to PTSD, Psychology Press, 2015

Austin Riede, Transatlantic Shell Shock, University of North Georgia, 2019

Fiona Reid, Broken Men, Continuum Books, 2010

David Stevenson, Cataclysm, Basic Books, 2004