Forensics in a Nutshell

Theresa Ryan is worried about her sister Maggie. She’s seen neither hide nor hair of Maggie for weeks. So she’s come to the boarding house where her sister is living on Copp’s Hill, Boston. Hearing no response to her call from the front door of the building, Theresa rushes up the stairway, only to come to a dead stop. The door to Maggie’s room is open, two empty chairs sit at the foot of the mussed but empty bed, dirty glasses lie on the floor. Attracted by the sound of running water, Theresa enters the bathroom, stumbling over an empty bottle, and shivers when she sees Maggie in the bathtub, fully dressed while water from the faucet falls onto her open blue eyes. Theresa shudders as the floor rattles and cracks open, the building shakes, and the room falls apart under the weight of a wave of thick, sticky liquid that smells like baked beans.

Dr. George Burgess “Jake” Magrath, medical examiner for Suffolk County, Massachusetts, hurries to Commercial Street at the base of Copp’s Hill. A massive industrial accident has released tons of molasses onto city streets, crashing buildings to the ground, burying men, women, and children, and leading to “unexplained deaths” he has the responsibility to explain. With him is a woman determined to provide help—his long-time friend Mrs. Frances Glessner Lee.

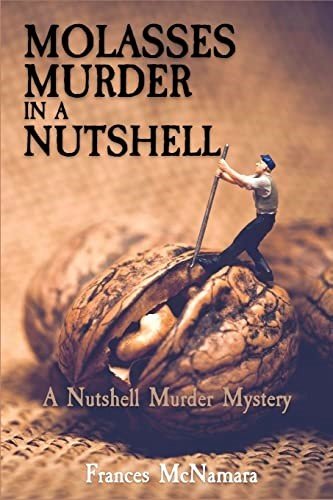

Together, Jake and Fanny pull together the details of the accident—The Great Molasses Flood of 1919—the crime scene around Maggie’s death and the identity of the killer in Molasses Murder in a Nutshell. Molasses is the first in a new mystery series by Frances McNamara, known for her Emily Cabot books. The book recalls the actual Molasses Flood and introduces readers to the important forensic work conducted by Glessner Lee and Magrath. The book and the mystery series build on a quote from Lee about forensics: “The investigator must bear in mind that he has a two-fold responsibility—to clear the innocent as well as to expose the guilty. He is seeking only facts—the Truth in a Nutshell.”

For this author’s book review, see: Molasses Murder in a Nutshell (A Nutshell Murder Mystery) - Historical Novel Society

The Flood

1919: the Boston Molasses Flood and the Year of Violence and Disillusion - U.S. Studies Online | U.S. Studies Online (usso.uk)

At about half-past noon on January 15, 1919, sounds of disaster reverberated down Commercial Street opposite Copp’s Hill in Boston’s North End—a sharp, metallic roar followed by rumbling, hissing, and finally the boom of an explosion that sent a 15-foot-high wall of molasses speeding at 35 miles an hour into commercial buildings, houses, the local firehouse. The thick sticky liquid snapped electric poles and the solid steel supports beneath the elevated train platform, knocked some buildings off their foundations, trapped, swallowed, and drowned pedestrians, residents, and horses. Though the wave of liquid quickly receded, it took days for rescue workers to find the missing and weeks to clean out the muck. In the end, the incident killed 21 people and injured 150.

The molasses, destined eventually for the manufacture of munitions, had been stored in a massive 50-foot-high, 90-foot-wide steel tank built and operated by Purity Distilling Company, a subsidiary of U. S. Industrial Alcohol. The accident, initially blamed on anarchists by USIA, was the result of negligence. Experts in court cases proved the tank’s steel walls were too thin, rivets were faulty and cracked under pressure, and warnings were ignored. One of those experts was Dr. George Burgess Magrath, medical examiner of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. He had been among the first responders on the scene and set up a field hospital and temporary morgue. He later testified about the causes of death: bodies crushed by debris, suffocation or drowning from molasses in their lungs.

Forensics Failures

At the time of the Molasses Flood, the individual responsible for investigating suspicious deaths in most jurisdictions was a coroner. But an extensive study of New York City coroners from the inception of the coroner system in 1898 to 1915 found that not a single one was qualified or trained to perform his duties. Only 19 of 65 coroners had been physicians, 18 were undertakers, seven were politicians, six were real estate dealers, two were plumbers, and two were saloon keepers. Among the rest were an auctioneer, butcher, musician, milkman, and wood carver. (Bruce Goldfarb, 18 Tiny Deaths, Sourcebooks, Naperville, IL, 2020)

Most conducted a superficial examination, if they did any at all. Many certified causes of death were patently absurd: The cause of death of one man was certified by a coroner as a thoracic aneurysm despite the fact that he had been holding a revolver and had a bullet wound in his mouth. (18 Tiny Deaths)

Police were not only untrained for forensic investigations, they often destroyed evidence at the scene—walking through blood, moving the body, handling the supposed weapon. Detectives were not much better: Nearly 25 percent of the detectives in Cleveland were considered to have the mentality of boys no older than 13. (18 Tiny Deaths)

Boston was the first city to establish a formal medical examiner’s office in 1877. The first person to hold the job of medical examiner was a physician, Dr. Francis A. Harris. The second was Dr. George Burgess Magrath, a specialist in pathology and instructor in legal medicine at Harvard Medical School who incorporated the latest and most advanced systems of death investigation after spending a year in London and Paris. (18 Tiny Deaths)

Gathering, interpreting, and presenting evidence from crime scenes were still highly problematic. A landmark 1928 study, The Coroner and the Medical Examiner, faulted legal medical education, noting “In not a single school is there a course in which the student [of legal medicine] may be systematically instructed in the duties…which may arise as the result of crime or accident.” (18 Tiny Deaths)

Glessner Lee and Magrath changed all that. Glessner Lee endowed the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard and supported the professor of legal medicine, Dr. George Magrath, beginning in 1932. In 1937, Dr. Alan Richard Moritz was named chair of the department.

The Nutshell Studies

In 1944, Glessner Lee decided to develop an intensive one-week seminar in the medical aspects of crime detection for the individuals most often called to crime scenes first—state troopers. The problem? Providing first-hand experience of crime scenes or tools that mimicked what they would see in the field.

Glessner Lee’s solution? 18- by 18-inch, doll-house-like wooden boxes or dioramas that presented crime-scene details in three dimensions. The first was based on an actual case—a man repeatedly had threatened to commit suicide by placing a noose over his neck, mounting a crate or box, and waiting for his wife to convince him to step down. Then, one day, the crate broke, and he hanged himself.

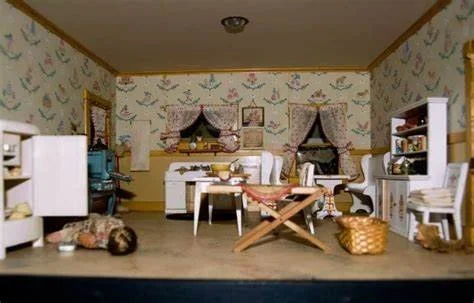

Glessner Lee created 18 dioramas, known as the Nutshell Case Studies. One called Kitchen. The corpse of a woman in front of a gas stove, gas jets open, doors locked, newspapers stuffed around the door frames. But: half-peeled potatoes indicated the woman was preparing dinner, a can of soda on the table and ice trays on the floor suggested the woman was preparing a drink for a visitor. Suicide? Maybe not.

Directly related to McNamara’s Molasses Murder is the Dark Bathroom diorama, inspired by a series of bathroom murders in England. A woman’s fully dressed body lies face-up in a bathtub, water streaming onto her face.

(Photos of the Nutshell Studies and details about their construction may be found in: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, by Corrine May Botz, The Monacellli Press, New York, 2004.}

In the seminars, police attended lectures about causes of death and the difference between blunt and penetrating injuries and an autopsy and interacted with the dioramas. Each police officer had 90 minutes to observe two of the dioramas and develop reports on them. As Glessner Lee explained, the diorama were not meant to serve as cases that needed to be solved. Rather, they were “exercises in observing, interpreting, evaluating and reporting,” illustrating the most basic requirement of crime scene investigation—resisting the temptation to jump to conclusions. (18 Tiny Deaths)

Outside of the seminar classroom, the dioramas have been featured in national magazines, beginning with an article in Life magazine in 1946 and The Case of the Dubious Bridegroom by Perry Mason author Erle Stanley Gardner. The Nutshell Studies themselves are still used to train police officers.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Molasses-Flood

https://www.history.com/news/the-great-molasses-flood-of-1919

https://www.boston-discovery-guide.com/great-molasses-flood.html

https://time.com/5500592/boston-great-molasses-flood-100/

https://www.npr.org/2019/01/15/685154620/a-deadly-tsunami-of-molasses-in-bostons-north-end

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Molasses-Flood

htts://www.history.com/news/great-molasses-flood-science

Goldfarb, Bruce: 18 Tiny Deaths, Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2020.

Botz, Corinne May: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, New York: The Monacelli Press, 2004.